Welcome to my website. If you have made it to this page, that means you figured out the controls

and were curious enough to wander over to the ticket machine. Congratulations! Now you're probably wondering what the point of this website is.

Well, my name is Calvin Laughlin, and I am a junior at Stanford University. I created this website from scratch, and it was originally going to be just about me,

but I chose to model it after the Caltrain for a few reasons:

One, I love the Caltrain. I don't think I've ever paid the fare but it's gotten me to San Francisco and back many times.

Two, in the spring of 2022 I took a class called CS111: Operating Systems taught by John Osterhout. In the class, we implemented a synchronization problem. In the problem, each thread

was represented by a passenger, and each train could only carry a limited number of threads. So, using a FIFO system we used locks and condition variables in C++ to manage the threads

and ensure that nobody got on the train before it was their turn to do so. It beautifully illustrated synchronization and inspired me to make this website as a visualization to that problem.

OTHER INTERESTS: Art History. Below, you can read a a piece I wrote connecting my experience with breaking my leg to the paintings of Vincent van Gogh. In short, presence is everything. What do you need right now?

calvin3@stanford.edu

(310) 871-2726

palo alto, ca

Friday, April 14th. The story begins with a visit to the beach on a sunny day, where I gazed upon a beach with waves from atop a bluff. The light and sea blues, the dusty yellow sand and the dark greens combined to create a beautiful scene with no shadows. On the beach strolled two people, aimlessly wandering. What I came to realize, though, is that this can be enjoyable to anyone–it does not take a master of perception to describe this as “pretty” because it is basically a postcard image. Van Gogh undoubtedly painted beautiful, awe inspiring scenes, but that was not the essence of what he meant with his painting. Vincent would have appreciated this beach, but so would everyone else; the power of Van Gogh lay in his ability to see the unseen, to hear the unheard, and thus feed the unfed. This is because, as stated by philosopher Boethius, with a fortunate environment, anyone can be happy, but the truth of one’s self only arises during the dark and tumultuous periods in one’s life (Book II, pt. II). Vincent faced it head on, for he built himself atop a solid foundation and came to smile at the raging storm. This quarter, I too faced a storm and took lessons from Vincent in an attempt to heal. Throughout this notebook of noticing, I will chronicle my journey to a broken leg and back, as well as how I came to know Vincent van Gogh a bit better along the way.

Sunday, April the 16th. It was a beautiful day, and for the first time on Stanford campus I decided to walk instead of riding my electric form of transportation called a OneWheel. During my walk, my mind was filled with worries and anxieties about the upcoming quarter. As I worried, projecting myself into the past and future, I unconsciously drudged on, just mechanically making my way across campus. On my way from Tressider, I passed by the Bechtel center and, amidst my worries, was struck with momentary consciousness. In front of me lay a small clearing, a Close, with a few trees and some shrubs. I felt as if I had seen the scene I gazed at before. And in a way, I had, since just a few weeks prior I was met with Van Gogh’s Undergrowth at the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam. At first glance, Undergrowth is a scene not unlike what I had seen on my walk. But upon further inspection, one begins to see what Vincent saw: a sea of color melding everything together into a citron green, ochre, flame yellow, and marine vibration. His brushstrokes layer color upon color, and if I were to step into the painting, I fear I would be engulfed; the ground gives out and the depth of the undergrowth seemingly has no end, like an infinite space filled with microscopic stars as bountiful as the sky, but shrouded by the shade of the trees and hidden away, calling no attention to itself. Within this tiny patch of seemingly insignificant shrubbery lay the entire universe. The moment faded, the real world crept back in, and I took my souvenir photo, continuing on my way unchanged. On 15 July 1889, from Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Vincent wrote to Theo on the topic of worry while he was painting Undergrowth: “Thus sooner or later we find our fate. But certainly for you, as well as for me, it would be a little hypocritical to forget completely our good humour… and to place too much weight upon our cares” (#790). Looking back, I did not know the privilege I held that day because I was bogged down with too much weight. I know now that my cares removed me from the earth; only for a brief moment was I able to revere my present moment, and otherwise I worried about my future, a concept impossible to control and bound by fate. If only I knew then that the real worries would come soon enough. The next day, I returned to my electric transportation device. The day after, I fell off it and broke my right leg in three places.

Wednesday, April the 19th. At dusk, when the sky began to darken, I stepped on my OneWheel and began my ride home. Next to Jerry there is a three-way junction with one path leading to the lake, one leading up the hill, and another leading to a parking lot. I took the middle road of the junction, as I had many times before, but somehow I was sent flying off my transportation and hit the ground. My leg twisted in a way I knew not possible, and I was left on the ground, helpless. I imagine Vincent to feel a similar way, not in a physical pain but a mental twisting and furrowing, working alone in the fields as he writes to Theo and Jo on 10 July 1890: “It’s no small thing when all together we feel the daily bread in danger, no small thing when for other causes than that we also feel our existence to be fragile” (#898). I had never felt so composed of glass. In emergency situations, the mind shifts to an intense conscious presence out of necessity. There is no concept of time, of worry, or of past or future because the present moment requires attention and is too overwhelming to let the mind wander. It is in these moments that we realize our human nature, that we are fragile, that we can break. I now contemplate the paths I could have taken, like Vincent’s Wheatfield with Crows, the left or the right, the past or the future, and how the third path, the middle path, where the end is unknown, is the one the crows flock to. The crows came to me in the form of EMTs, taking me away to the hospital. Now, as I reflect, I simultaneously find something “healthy and fortifying” (#898) about the junction. In the midst of the terror and loneliness, on that middle path there is a mystery to be carried by fate; my accident was no accident, but rather the result of a long path I had been traveling my entire life. Vincent, too, accepted the tumultuous path he had trodden, and I like to imagine him painting Wheatfield with Crows with a similar sense of uneasiness yet stillness. As I look at the scene, I feel no fear nor anguish nor regret. This is my path, and this is how I must travel.

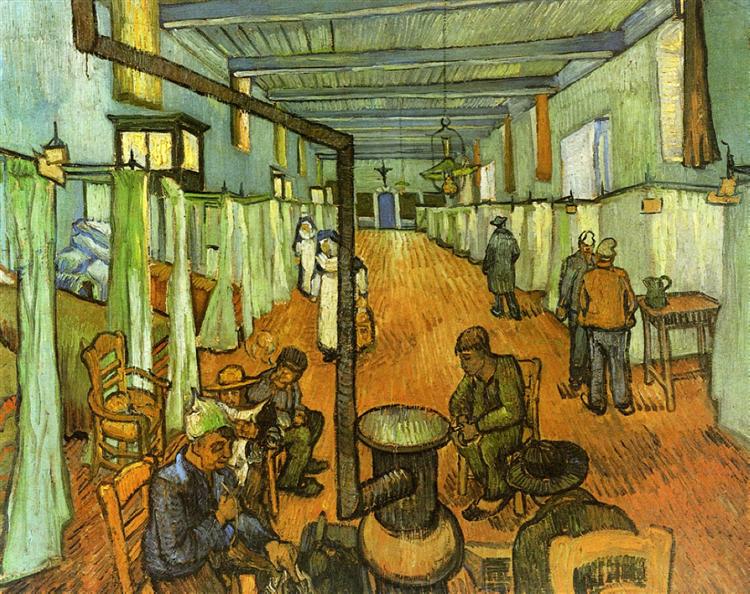

Thursday, April 20th. I was woken up early, at around 6am, to prepare for my surgery. I woke up to the presence of my mother and the most beautiful sunrise. On the horizon was a deep orange that faded into a sunflower yellow and, more vertically, a soft, light blue that became progressively darker as if black paint was mixed in. The sun would arrive soon, and with it would come a radiance that filled the room. Vincent spent far longer in a hospital than I did, and he was still able to be the sower, a bringer of light and truth, able to observe, feel, and record the motions of beauty, emotion, and pain. The light from the horizon flowed through him to depict a naive truthfulness, as seen with the paintings he completed at the hospital at Arles, such as The Sick-ward. The Sick-ward presents a cross at the vanishing point, namely Vincent’s belief in something more, something deeper than labeling everything as a microbe. This belief isolated Vincent, but he continued to give himself to the world, reverberating throughout time. Later that day in the hospital, I was cleansed of any microbes and received a tibial intramedullary rod, which is a metal rod placed within my shinbone from knee to ankle.

Friday, April 21st. I returned from my stay in the hospital and was placed in a splint and bound to a wheelchair with occasional crutches. In a wheelchair, you notice every bump, every slight angle in the ground, every possible hindrance. It’s overwhelming, the impact of each bump causes a vibration that is felt to the very bone, each crack vying for attention. Like Vincent, I felt “my life is attacked at the very root, and my step is also faltering” (to Theo and Jo, 10 July 1890, #898). Literally, my step was faltering, but also my goals and ambitions had been thrown into a freefall. In a feeling like Vincent’s being dismissed as a preacher in the Borinage, I was denied my ability to go to class, to see my friends, to do even basic tasks. I didn’t know what lay before me, and I was afraid. However, in a wheelchair, you are more equipped to notice the beauty of the ground we walk on every day. The small insects, the little shrubs, the patches of dirt we pay no mind. Each square foot of the earth is a little universe, an ecosystem, all to be exalted slowly. It is only when you lose your ability to walk that you realize the complexity and beauty of the ground beneath your feet. As I wheeled around EVGR, I initially feared the cracks in the pavement caused by underlying roots because they would cause intense uncomfortable vibration to my leg every time the wheels of the chair passed over them. These bumps are the movements of life, the challenges we all face that rock our beings to the core. Yet within these bumps lay beauty, roots of a tree winding through them, a love for all that is. Eventually, instead of despising the bumps, I came to accept them as necessary to life and see the beauty that lies beneath them. The undercurrent of the bumps is a natural order and beauty. The vibrations they cause are reminders that we are alive, that we are in the world and that even the smallest things can cause simultaneous ecstasy and pain.

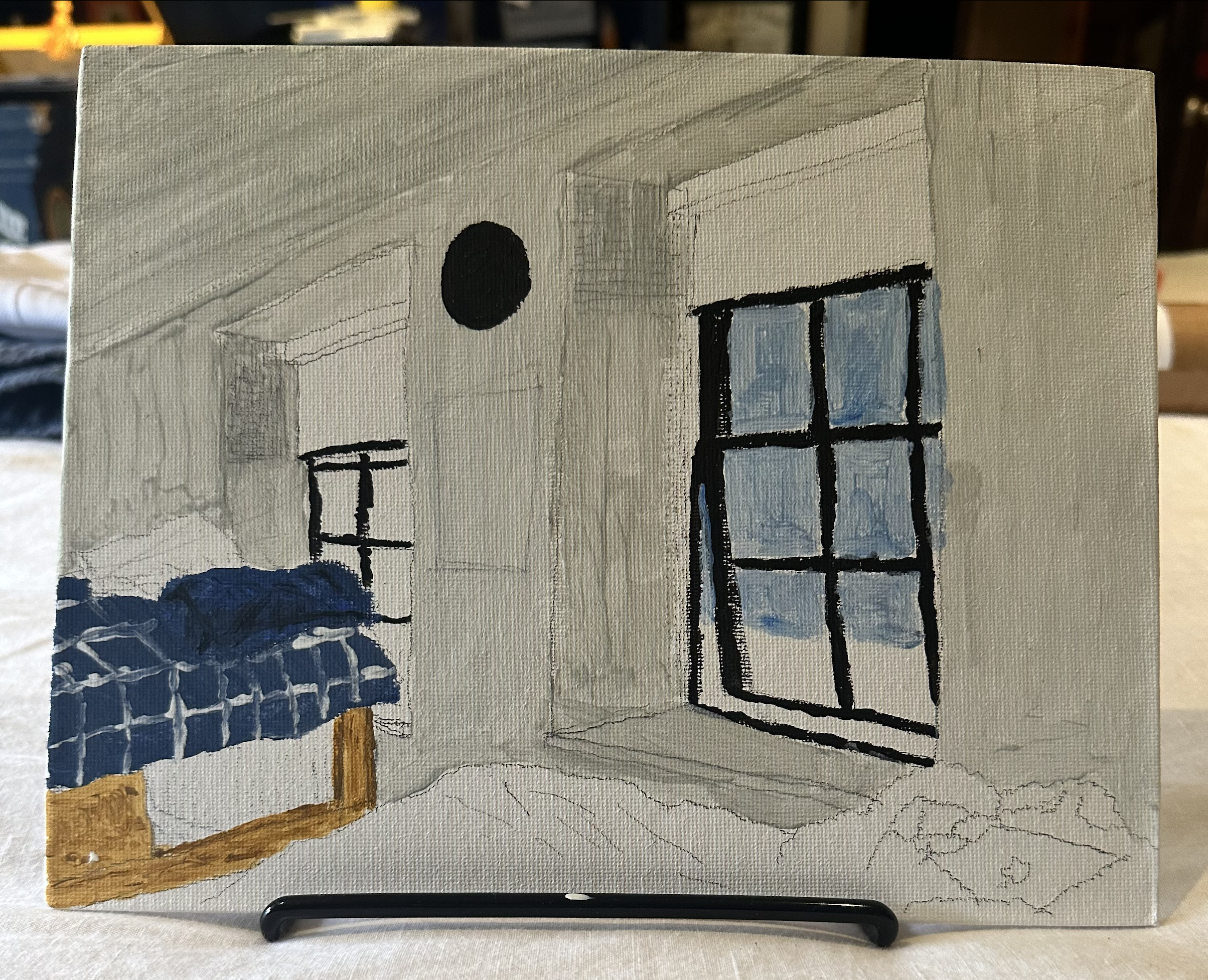

In the weeks after my surgery I was largely confined to my bed. I was confronted every day with the same scene: windows, wall, clock, poster, chair, blanket, computer, bed. Naively, I was initially very bored and somewhat depressed at the sight of the same scene all day, every day. They all blended together, and in the labels of my mind I saw them each as means to an end. I felt a prisoner of my room, much like Edmond Dantes of The Count of Monte Cristo (1844), wrongfully imprisoned for an accident. However, while imprisoned, Edmond meets another prisoner named Abbé Faria, a former priest. Edmond laments his position: “There are 72,519 stones in my walls. I've counted them many times.” Faria reminds him of the wonder of life: “But have you named them yet?” It is not enough to count things, or to simply observe; true understanding comes from attaching significance to the seemingly insignificant. Vincent saw his own bedroom in a way similar to Faria. In a letter to Paul Gaugin in October 1888, he writes of his completed Bedroom in Arles in stunning detail: In flat tints, but coarsely brushed in full impasto, the walls pale lilac, the floor in a broken and faded red, the chairs and the bed chrome yellow, the pillows and the sheet very pale lemon green, the blanket blood-red, the dressing-table orange, the washbasin blue, the window green… (#706) Van Gogh’s world was one of increasing disintegration. With other post-impressionist artists such as Cezanne and Seurat alienating existence by separating the real from the depicted, evaporating the true world, Vincent desperately clung onto existence, objects, and the real. There came a sanity and clarity from knowing that objects exist and that they have meaning. Painting strong dark lines around objects to establish them, they went from means to an end to an end in themselves, and in doing so Vincent became not just an artist of the real, but also a carpenter of reality. I do not possess the same ability for color and shape that Vincent had. I attempted, but before I could finish I had to move out of EVGR, and thus the painting is stuck forever in that transient state. I learned to appreciate objects and my surroundings, because even a static environment contains within it infinities beyond comprehension.

Saturday, May 13th. As it turns out, it is wildly unsafe and impractical to have a person with a broken leg living on the 10th floor of a building. Therefore, I was lucky enough to find space to live in Narnia, my old place of residence. I moved back in, and upon moving in I was struck by the beauty of the building and how it is situated in nature. Van Gogh also moved into his yellow house during the month of May in 1888 and held a similar sentiment, believing the building to be “tremendous, these yellow houses in the sunlight and then the incomparable freshness of the blue” (to Theo, 29 September 1888, #691). It seems that it is the juxtaposition of the two colors together that makes their vibrance shine brighter. As is the same in life, that the joys of the world can only be experienced when compared to pain. Without pain, there would be no joy, it would not exist, in the same way that without nothingness, or emptiness, there would be no presence.

Tuesday, May 9. I exchanged my splint for a walking boot, granting me the ability to walk (somewhat) using crutches. The wheelchair is gone, and with it I lost the same sense for the ground and what lay below me. I try to remind myself to appreciate it as much as I can, but when everything in the world demands attention it can become overwhelming, every object singing its song. Van Gogh had an affinity for shoes that other artists of his time did not. Perhaps it was his ability to perceive all things in life, even those as inconsequential as shoes. But his portrayal of shoes is particularly interesting because of its psychological power; in the rugged shoes lay the story of a hard worker, an individual who toils each day and is beaten down. Perhaps the shoes are influenced by his time in the Borinage with the coal laborers or by his own tough path in life. In a Heideggerian sense, the shoes are what connect the world to the earth; for me, the clunky boot is a human effort to try to facilitate a natural process. I walk slanted, I feel unnatural, I am disconnected, and when I am out of my boot to place my foot on the earth, I feel a sensation on every muscle that was not felt before. A sensation of freedom and connectedness. Vincent writes about working on a “still life of an old pair of shoes” in a letter to Theo in August 1888, and later talks of the tough times he had been facing: “But what can you do, sometimes I feel too weak in the face of the given circumstances, and I’d have to be wiser and richer and younger to win the fight” (#671). When I looked at my boot, I felt the same. The challenge of my leg seemed insurmountable, and each day challenged me. Van Gogh could have been justified in giving up his career as a painter for all the reasons he stated above, bottling up what he felt and pursuing a “real” occupation in the reality based world. However, he did not, because he chose a life of “active melancholy” rather than idle despair (to Theo, June 1880, #155). Vincent urges us to see the beauty, embrace our paths, and to rage against the dying light.

Throughout the month of May, I was offered to use Stanford DisGo, a golf cart service that provides rides across campus for those whose mobility is impaired. Through this service I met Juan and Cynthia, drivers for DisGo. Through our trips across campus, I came to know them both well. They were my link to the world, my only way of leaving my room. Much like Vincent’s postman friend Joseph Roulin, they were assigned to me in the same way a postman is assigned to a house. What started out as an impersonal job soon became a friendship, and instead of delivering mail, Juan and Cynthia delivered me to where I wanted to be. Roulin was Vincent’s link to his brother and those he cared about, and the same goes for them with myself. It was through making a new connection after my isolation that I was able to better understand why Vincent wanted to paint portraits of the Roulin family. As he writes in a letter to Theo in September from Arles, “I’d like to paint men or women with that je ne sais quoi of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations” (#673). As in the Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin, Vincent aims to show the goodness and humanness within everyone. The universal human connection is what binds us, a permeating truth that is visible through compassion, helpfulness, and gentleness. Through Vincent’s portraits he portrayed this sentiment, and through my connections with Juan and Cynthia, I felt it.

Tuesday, June 6th. This brings us to the end of the journey. My boot is removed and I am placed back in regular shoes. I still walk with a crutch, but on the surface I appear somewhat healed. I often sit down by the lake with friends, sometimes in a hammock, and we watch the sun set. Once the sun disappears under the horizon, the yellow lights turn on and reflect off the still black water. The stars are not visible because of the light pollution, and the moon is often behind the clouds. Through this journey with my leg, I have learned to stop looking for the magnificent stars just in the sky. The universe and all the cosmos lie in front of me, everywhere. They are not somewhere far off in the distance, but instead reflected off the water, brought down to earth and embodied as light. It is the job of the artist to perform this feat: to reach up beyond what is possible, to bring down the light and beauty, and to reflect it and reverberate its message across the world. When I look across Lake Lagunita, I see Vincent in the water, accepting the world as it is and taking it down into its depth, only to give it back to all of us as he sees it. Beauty is all around us. We have been conditioned to become blind to it, to hear it but not listen. It is only through the process of death that we are allowed to survive; only with darkness is there light, and only with pain is there goodness. The artist is the lightning rod that is able to magically transform these two opposites into one being: existence. And not an unconscious existence, but rather one where everything has meaning, where every step is a betterment along the path, and where the seemingly insignificant ant is as beautiful as a mountain. Vincent van Gogh has given me the ability to see the world as it truly is, a divine afterthought that contains within it a melancholy ecstasy that is always present but rarely seen. It is only after a great storm that the warmth of the sunlight is appreciated, and I am grateful for all that has happened to me, and most of all grateful for this present moment.

(c) calvin laughlin 2022 all rights reserved (all of them).